Pondering on the intermingling of exo and endogenous processes rooted in external recognition and territorialization, respectively, to link historical and contemporary politics in the D.R.

The Dominican nation-state emerges embedded in a wider, racially charged, geopolitical setting where sovereignty is subjected to regional, neocolonial dynamics; and, relatedly, with the urgency of consolidating the state through the territorialization of political power in a place where authority had been decentralized for at least two centuries prior to the emergence of the state.

Out of this political decentralization emerge the conditions of possibility for (1) the establishment of another colony and later state on the island (Saint Domingue/Haiti) with a vastly different socio, political and economic development; (2) fugitive geographies and the emergence of a free, necessarily mobile, self-sufficient peasantry in Santo Domingo outside the purview of the colonial and later state administration; and (3) a climate of political instability and endless coups as the next strongman or caudillo claimed control of the state.

The second point represented a great obstacle for proletarianization, introducing the need of importing foreign labor (particularly Haitian) for the development of the modern sugar industry in the DR, an enclave capitalist formation revitalized through foreign (particularly US) capital. And the third point prevented the protection of these investments. The inability of establishing a strong central state in the DR eventually resulted in the first US occupation, during a time when Haiti was also US-occupied territory, facilitating the establishment of a binational labor system supplying Haitian labor to work in the sugar industry, and doing some of the work of institutionalizing the border.

One of the things that I have failed to consider or emphasized on previous personal reflections is how localized—how gradual and partial—the development of a capitalist mode of production was through the case of the sugar industry. The consolidation of the territorial, centralized state and its role of incorporating a mobile, self-sufficient peasantry into the national project intersects or complements this story in interesting ways.

This population and space [el monte]—rooted in colonial fugitive geographies and “empty,” unoccupied, unproductive, untamed land/nature—were considered a problem before the nation-state. Indeed, the reason why the colony—often compared to neighboring and prosperous Saint Domingue—and later the nation would not progress according to colonial and early state intelligentsia. The need to control this unruly population by anticipating the need for labor and creating the conditions for capitalism to function in the state more broadly, seemed an apparently necessary requirement to safeguard sovereignty (official sovereignty at the very least) in the context of foreign and U.S. capital investment. The process of dispossessing and trying to fix the peasantry in space started during the U.S. occupation by way of a land registration system, but it wasn’t until the Trujillo dictatorship that the process of consolidating the territorial state and incorporating the peasantry into the national project took place. Trujillo built his basis of support during the first years of his regime through the peasantry by reconciling the restructuring of rural life that had been waiting to happen for a long time, with an alternative project of modernity that afforded certain concessions to the peasantry [policies of land distribution, agricultural assistance, and property reform] integrating them—unevenly, and not always successfully, but to the largest extent to date—into the national project as “men of work.” Trujillo is also known for being the most ruthless advocate of anti-Haitian sentiment, a textbook example of which is the 1937 Massacre, when he ordered to kill Haitians at the border.

Given the contrasting realities of Saint Domingue and Santo Domingo, the east’s precarious administration and land availability provided refuge for enslaved peoples and folks escaping the colonial structure on both sides of the island. As such, I see the border as a mechanism that not always reproduced a neocolonial logic in this setting. In fact, one that even facilitated emancipatory politics, opening avenues for the realization of liberated futures. The border, an area of historically fluctuating imperial and postcolonial jurisdictions was a squatter ground as isolated and separate from the nation as el monte had been. Trujillo’s orders are part of an effort to “dominicanize” or nationalize the border and come in the context of localized resistance against the central state’s decision to carry out deportations in the border zone transnational communities. As these ‘unofficial spaces’ were increasingly disrupted by the central state, in the border zone and throughout, bateyes became one of the few legal spaces for Haitians and ethnic Haitians to reside. As economic restructuring and increasing waves of migration would pushed them out of these secluded spaces and the restructuring and colonization (rather than incorporation) of dissident communities, state and elite crafted anti-Haitian discourse becomes hegemonic in the space of an increasingly all-encompassing nation.

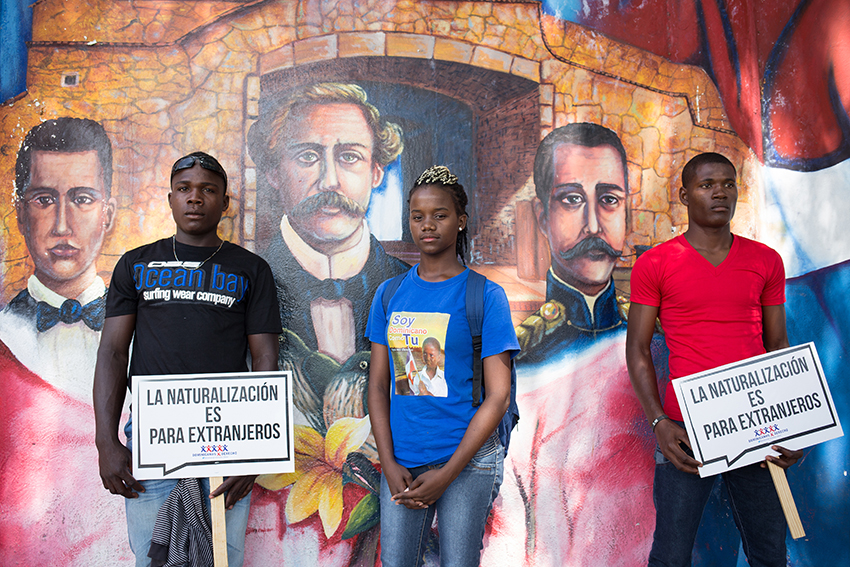

The legalistic and constitutional foundation of the ruling represents a novelty, a sophisticated change in the strategy of the ultranationalist right against the political recognition of ethnic Haitians, seeking to institutionalize policies that were previously enacted through violent, extra-legal, and arbitrary means.