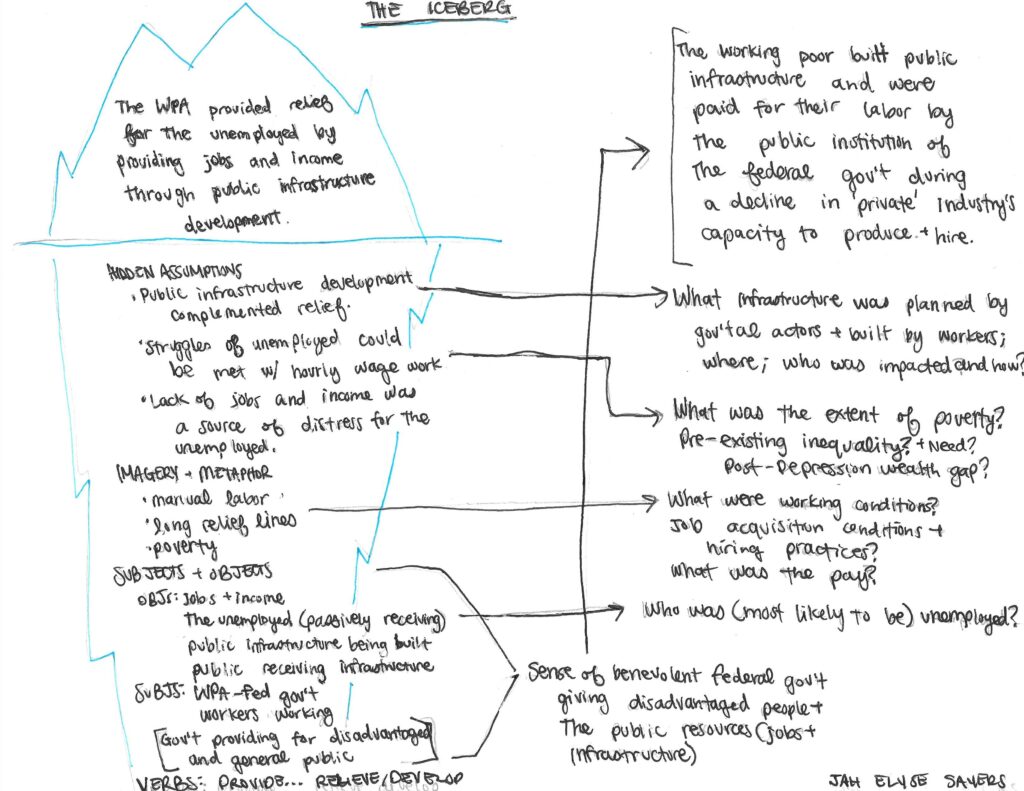

While HOLC’s residential security maps get flagged in general opinion as the origin of redlining and its maps take on almost iconic status, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) is often put forth as an example of good progressive federal policy. I use the iceberg method from Culture Hack (thanks, Diane!) here to draw out some questions from a typical description of the WPA before starting to look at its landing in West Philadelphia specifically.

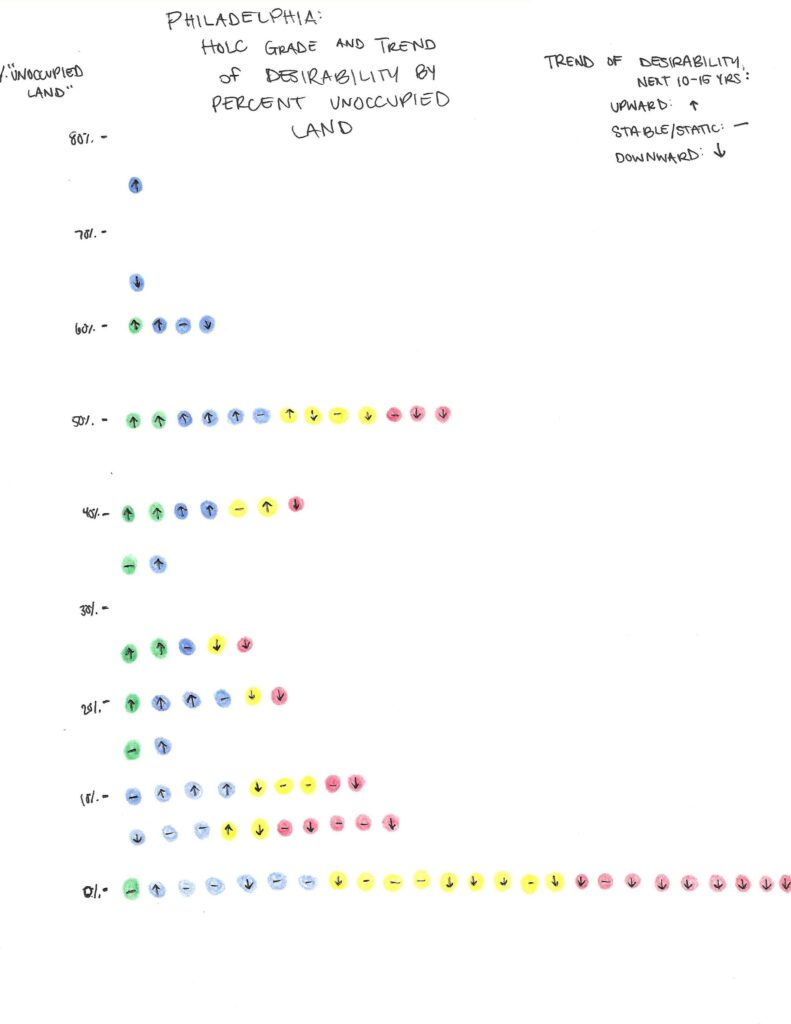

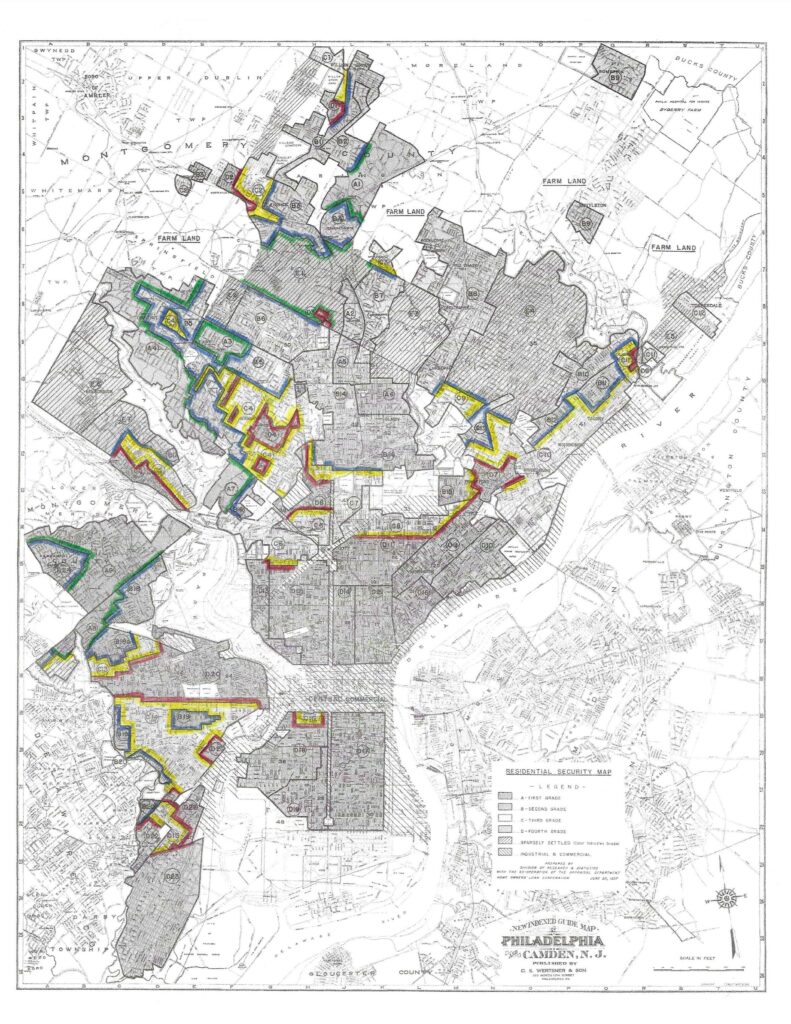

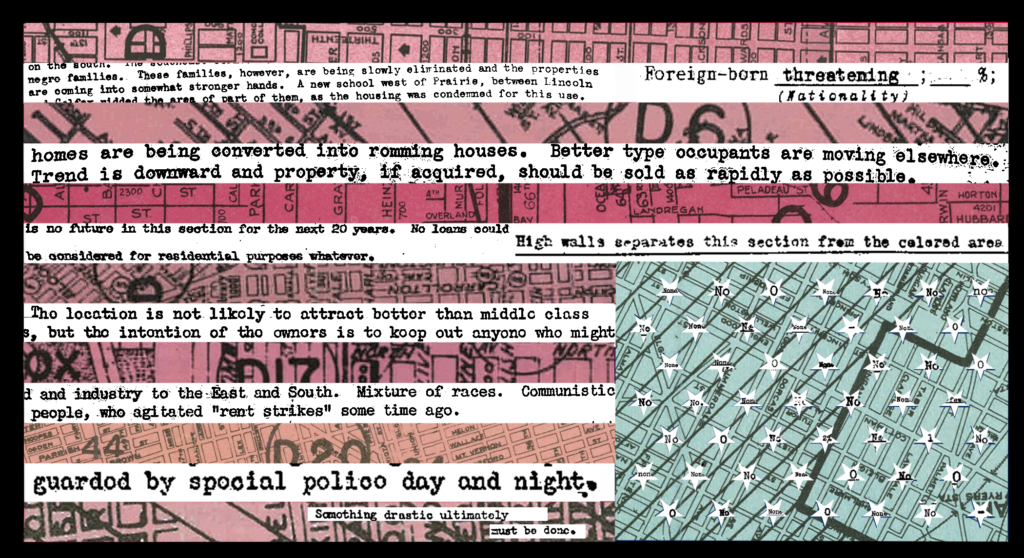

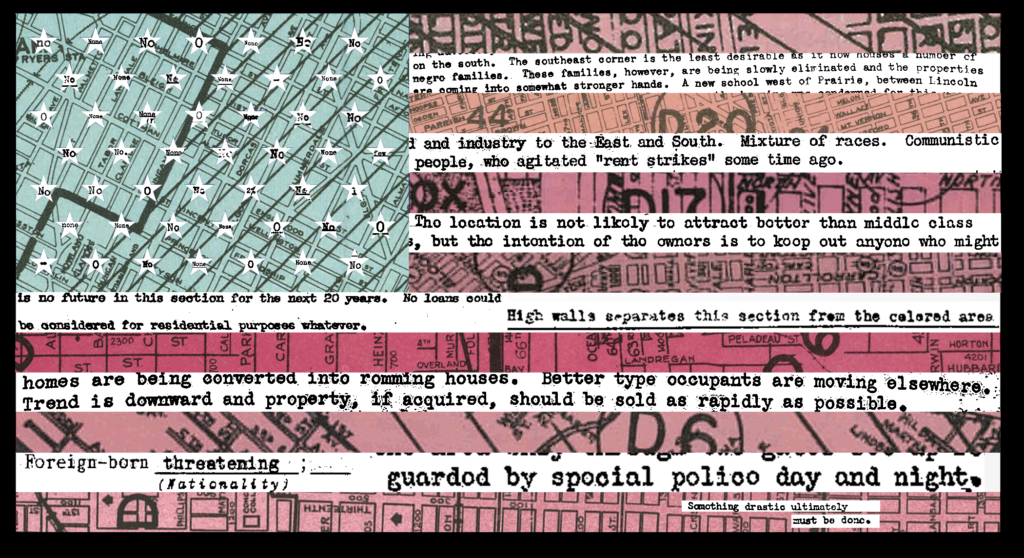

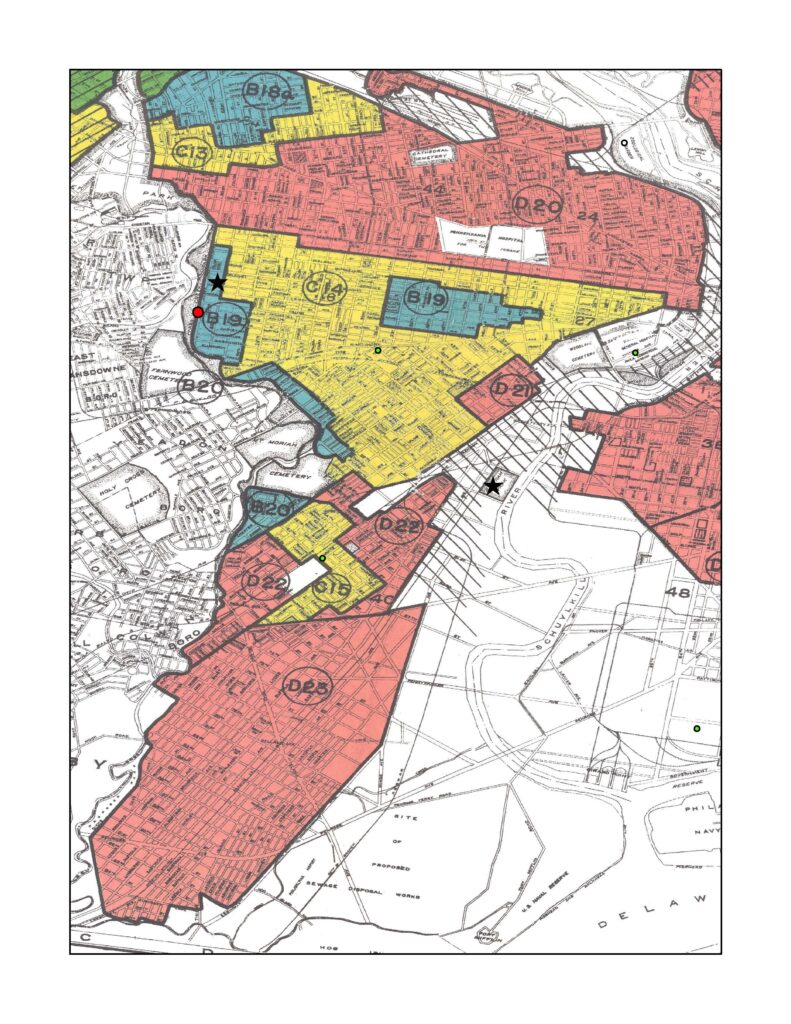

I want to zoom in on the assumption that public infrastructure development complemented the idea of relief for the unemployed by looking at what that public infrastructure looked like in West Philadelphia specifically. Using the Living New Deal map, we see a post office with art, two nearly co-located schools, and a guard house. Overlaying with HOLC’s maps shows the schools in a “yellow” area (C15), the post office also in a yellow area (C14), and the guardhouse in a blue area (b19). The map below (it’s a working draft and I know the symbology is far from perfect!) shows the schools and post office both depicted by small green dots and the guardhouse marked by a larger red dot. Before we get into the two stars depicted on the map below, I want to consider some of the implications of this “public infrastructure development” enabled by the WPA. Specifically, were WPA workers receiving the benefits of their labor beyond wages? Was the infrastructure for them (i.e. were they part of the public)? The area description for C14 describes the presence of “relief families” as “moderately heavy” and in C15 as “moderate.” In B19, their presence is described as “nominal” (Nelson et. al.). This does suggest that residents of the areas in which these WPA-built infrastructure projects were sited were also, in part, WPA workers, though certainly to a lesser degree than in nearby D22 and D23, which were reported to have “very heavy” presences of relief families. Notably, C14, C15, and B19 all report no Black residential population, though potential Black residents are reported as “threatening” in C14, the site of the post office. Again, this is in contrast to D22 and D23, reported respectively as 35% Black and 80% Black. “D” areas in West Philadelphia seemingly saw zero development as a result of the WPA, though residents presumably labored for hourly wages through the program. (What uneven temporalities are at play when considering the hourly wages and built infrastructure of WPA and built-environment and generational-wealth impacts of HOLC’s program and logics?)

Thinking about the impact of this WPA-built construction on mobility and security, we might see a post office as supporting mobility of information and items, and schools also as improvers of mobility (though specific inquiry into this school’s relationship to segregation should follow). A guardhouse for the Fairmount Park Police on the other hand, would pose a threat to the mobility of Black, non-white, immigrant, poor, and working class people while possibly offering a sense of security to white property owners and thus working within the logics of a segregationist approach to housing and lending per redlining and HOLC’s legacy. This “B” area is small and on the edge of the city boundaries, with C and D areas butting up against it. Within the tract, there was already an “Infiltration of” “Foreign-Jewish” residents, according to the area’s assessment. We might read the siting of a guard house here as guarding not only a sense of the “white collar class” residents’ security, but also guarding the residential securities–as in a collateralized fungible, negotiable financial instrument–mapped by HOLC in the interest of lenders.

What I didn’t know when I first learned about the guard house, was that I’ve spent the majority of my mornings these past six months on its grounds. It marks the beginning of creek-side trails I run frequently and anchors a park area with a wildflower field where my partner and I spent some of our best hours this past summer. Today, the building houses the Cobbs Creek Environmental Education Center, established in 2002 following advocacy, planning, and fundraising efforts led by a science educator and then-Cobbs Creek resident, Carole Williams-Green.

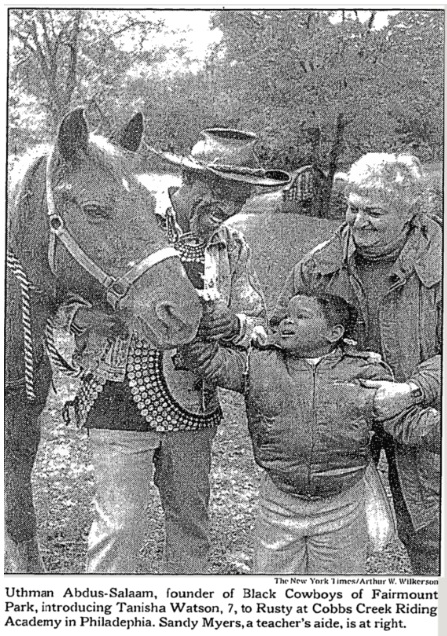

The most prominent media referencing the site is about the killing of a police officer there in the summer of 1970 (the area is described as “a black neighborhood”) shortly before the 1972 consolidation of the Fairmount Police and Philadelphia Police Department under Frank Rizzo left the guard house and its police horse stables “abandoned” (Janson, 1970; Kyriakodis, 2014). Information is scattered and sometimes contradictory, but I’m continuing to research the use of the building between 1972 and 2002. What I can gather is that a group called the “Greater Phila. Karate Institute & Cobb Creek Riding Academy” was founded in 1973 with its address registered as “63rd & Catherine Sts, Cobbs Creek Stable,” and a man named Uthman Abdus-Salaam and known as “Brother Sensei” taught free horseback riding classes to Philadelphia public school children, specifically children with disabilities. Mr. Abdus-Salaam was also the founder of the Black Cowboys of Fairmount Park respected member of the martial arts group, Universal Song Do Kwan Alliance.

What iterations of security, sovereignty, territory and mobility span the history of the building as a WPA-built police station in a white area; a police station closing in a Black neighborhood; the maintenance of stables and creation of riding classes and karate classes by Black cowboys and Black martial art instructors in a Black neighborhood in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s; and the creation of an environmental education center in a Black neighborhood in the 2000s to present day? Also, amongst widening calls to defund the police, what models do we already have for decommissioning of police infrastructure and appropriation and reuse by local communities? A 1987 New York Times article on Abdus-Salaam points to the stables’ financial struggle as he offers free classes and cares for the horses and aging stables. What might the resources, beyond the building itself, once allocated to the Fairmount Police have made possible for the building’s subsequent occupants?

To return to those stars on the map, they show two other West Philadelphia sites of mobility and resistance: MOVE’s Osage Ave. location and Sankofa Community Garden. In addition to the Cobbs Creek stables, I’m interested in further researching articulations of security, sovereignty, territory and mobility as pertains to both groups; MOVE’s centering of a philosophy that all living things move and the greeting “On the Move,” and Sankofa’s drawing on the Akan phrase “se wo were fi na wosan kofa a yenkyi,” or “it is not taboo to go back and fetch what is at risk of being left behind” and insistence on food sovereignty for African diaspora communities in West Philadelphia.