In 2010, the Dominican constitution was modified, eradicating birthright citizenship for children born to undocumented parents. So, if someone was to give birth in the Dominican Republic but their migratory status was considered irregular, the legal ambiguity of the parents is automatically transferred to the child, effectively creating a new category of under-citizenry for people born in the country. This constitutional change is preceded by unofficial state practices that arbitrarily denied state documents to Dominicans of Hatian descent. The case of Juliana Deguis Pierre is an often cited case for what would be a very consequential outcome: as she headed to a local state office to request an identification card in 2008, state officials confiscated her birth certificate, informing Juliana that an I.D. card could not be issued due to her French surnames—a marker of Haitian origins indicating to state officials that she was irregularly enrolled in the civil registry. Juliana filed a suit with a local court in 2012, but because she could only produce a photocopy of her birth certificate, her claim was declared inadmissible. She appealed the court’s decision and the Dominican Constitutional Court—also a byproduct of the 2010 Constitution—picked up her case a year later. Upon reviewing Juliana’s case, the Court stated that the Dominican Constitution denied birthright to individuals born to foreign diplomats and people “in transit” since 1929. While the language of “in transit” first appeared then, it was not until 2005 that a definition for this term was provided and legally codified through migration law No. 285-04. Before then, the term was loosely defined and inconsistently applied. But despite the ambiguity behind the term “in transit,” that was the excuse that allowed the Court to delegitimize Juliana’s claim to citizenship, and as it turned out, that of so many others. As a result of Juliana’s case, the Court ruled the controversial legislation TC 168-13, which retroactively stripped away the citizenship of Dominicans born to undocumented immigrants going back as far as 1929.

What crises are folded into this crisis? This is a question I have been pondering about as I think about a scenario in which denationalization is possible, and whether it represents a moment within a larger conjuncture. What cumulative tensions, spaces, and temporalities are condensed into this moment? I would like to spend time during what is left of this semester doing some of the preliminary thinking and assembling necessary to decide whether conjunctural analysis is a useful lens to analyze this case.

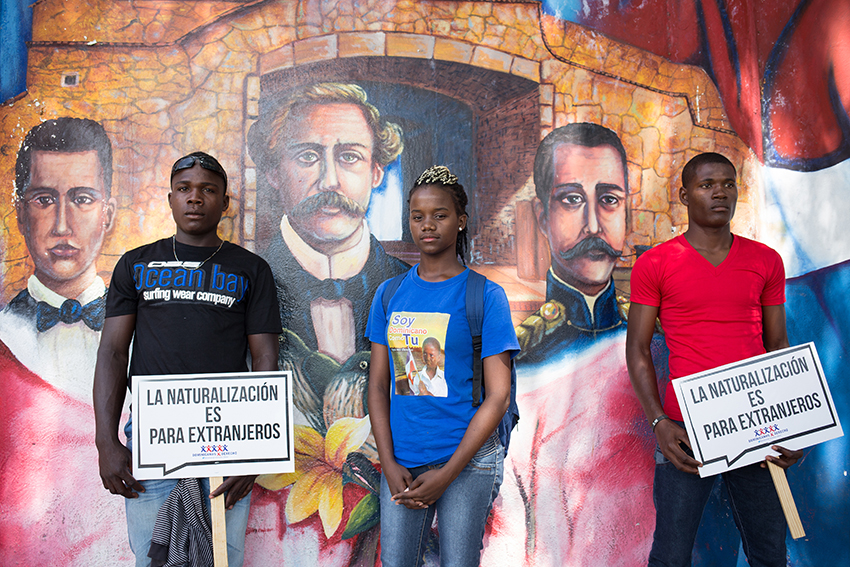

The ruling and constitutional change has often been perceived as a solution to a problem, a necessary evil of sorts to begin to manage undocumented Haitian migration. The new citizenship policies could surely have the effect of discouraging immigrants to settle in the country, and its discriminatory nature and retroactive application has already proven to have catastrophic effects in the lives of the denationalized population. However, the ruling itself does nothing to regulate border flows or put an end to the circular migration that furnishes cheap labor to the agricultural industry, construction sector, and domestic work, primarily. It reaffirms, through exclusion, the power of the state to decide who belongs or does not belong to the nation as a legitimate legal authority guaranteed by sovereignty in a framework of national v. international law.

The language of sovereignty and constitutionality—despite its legal violations—are useful mechanisms to legitimize and position the ruling in the service of law, order and non-intervention. It taps into what I recognize to be two central anxieties present throughout the history of the Dominican nation-state: Sovereignty or lack thereof as the nation carved space for itself in the racialized climate of 19th century geopolitics as postcolonial independence seriously threatened the colonial power structure; and the political instability that would follow, often in the form of undemocratic rule,carrying the nation into the twentieth century at the mercy of coups, foreign interventions and dictatorships. These anxieties have often manifested in tandem, or rather in an entangled manner in which undemocratic rule—associated with a weak institutional state—could justify an assault against sovereignty that generally concealed and served foreign (though not exclusively) socio-political and economic interests at the expense of popular wellbeing. Given this history, the affective register around questions of sovereignty and procedural protocol are generally regarded as something to be defended and respected at all cost. It also interweaves, in my view, questions of sovereignty as an abstract political principle of external recognition with a grounded analysis of internal territorialization encapsulating the process and obstacles to state modernization and centralization, and the discourses of security attached to both of these concerns. As I reflect, I find myself thinking about different moments in which this discursive architecture might be at play, resulting—as with denationalization—in the erasure of the political recognition of racialized subjects, through the dual motion of state expansion and nation shrinkage. In subsequent blog posts, I will seek to elaborate on these different moments to test the explanatory power of this line of thought, and benefit, whether it proves to be an appropriate analytical lens or not, of the generative stimulus it has provided thus far.