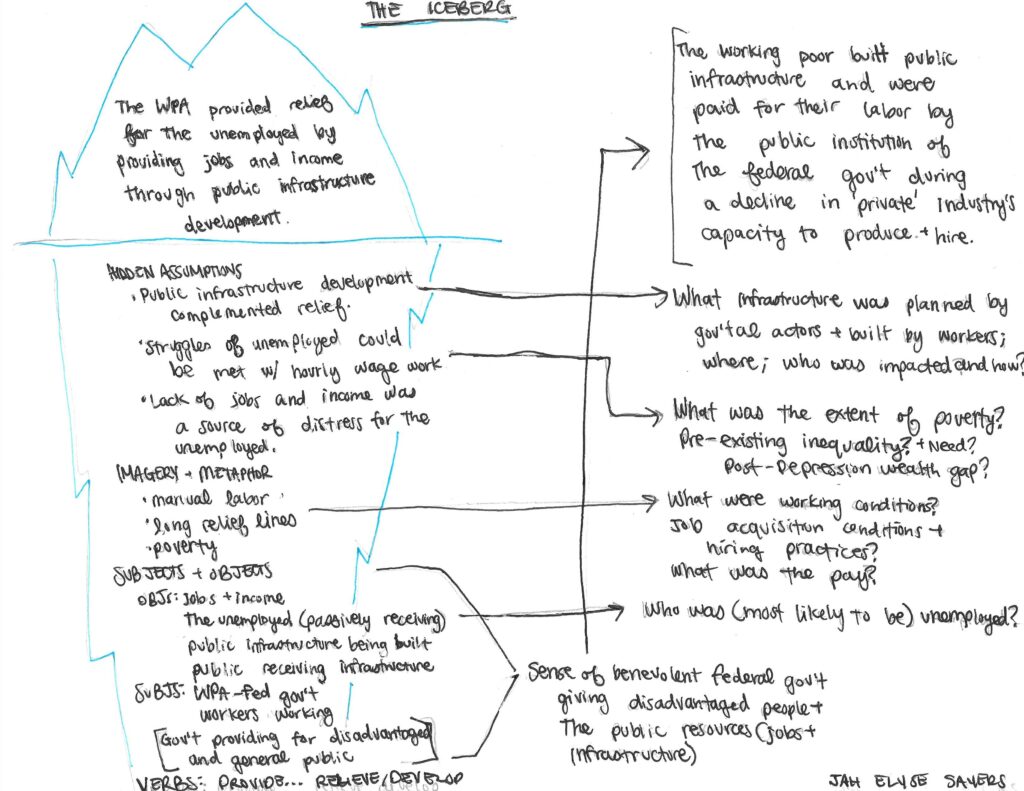

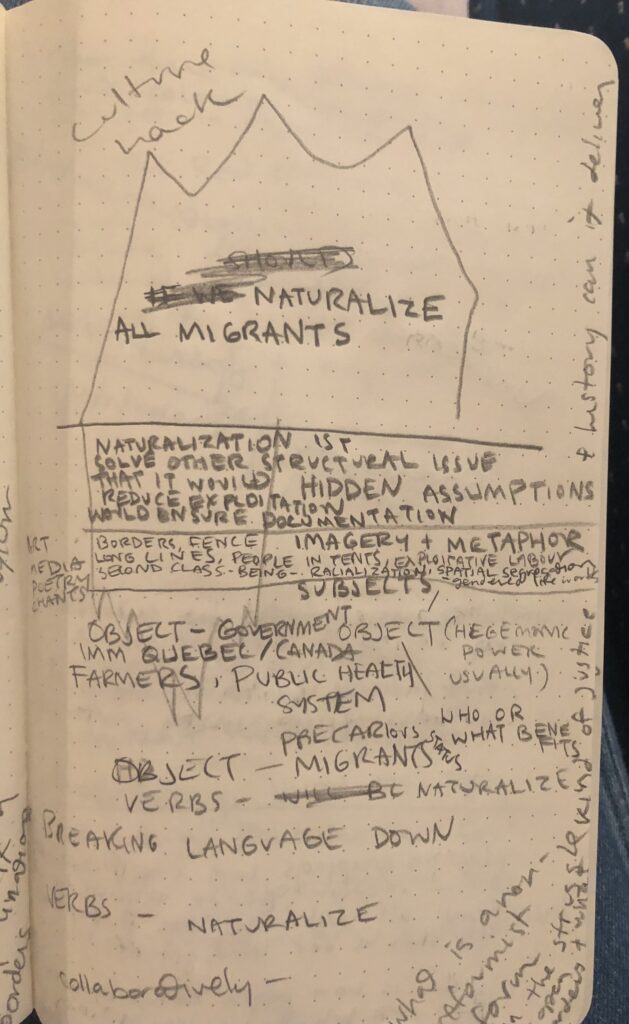

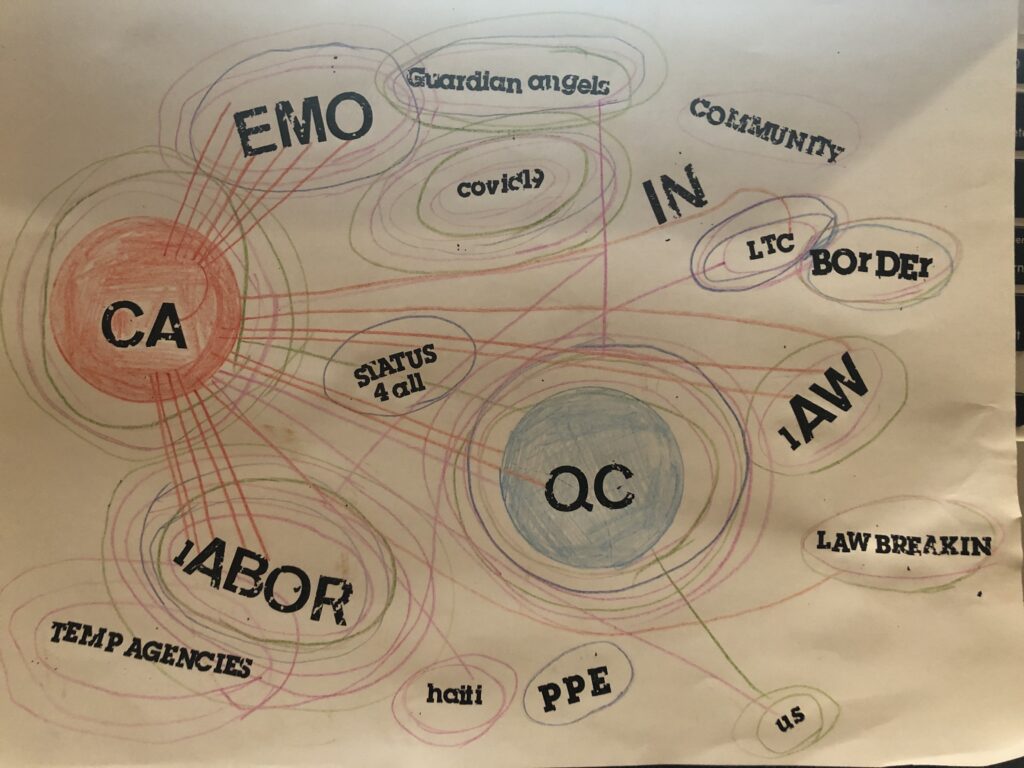

Diane shared with us the method of the iceberg, that she learned from friends doing organizing work. It is a great method to question basic assumptions about our cases. It allows us to think first of all about the main assumptions on which our work relies. It then obliges us to deconstruct it and go to the roots of our way of framing it.

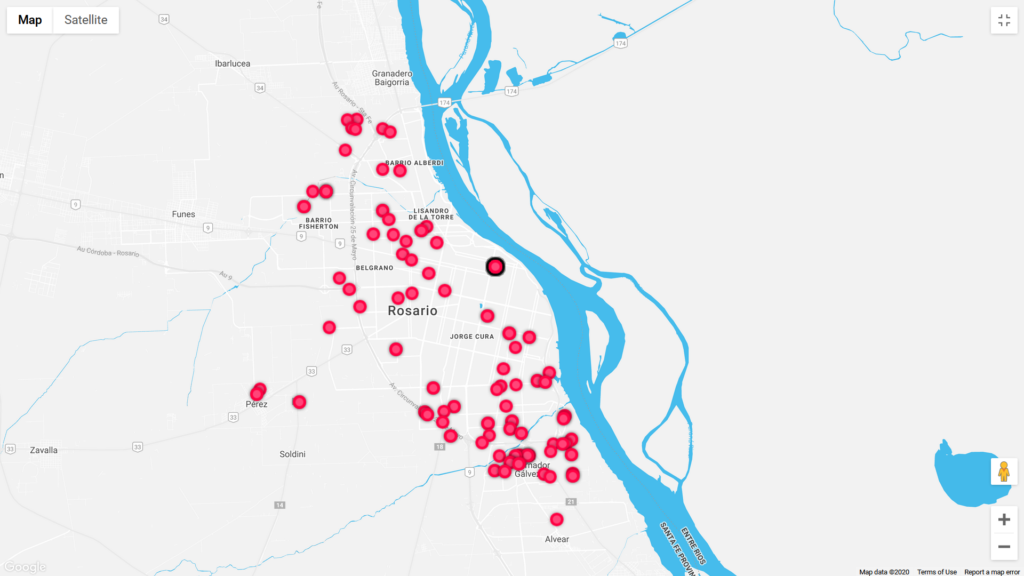

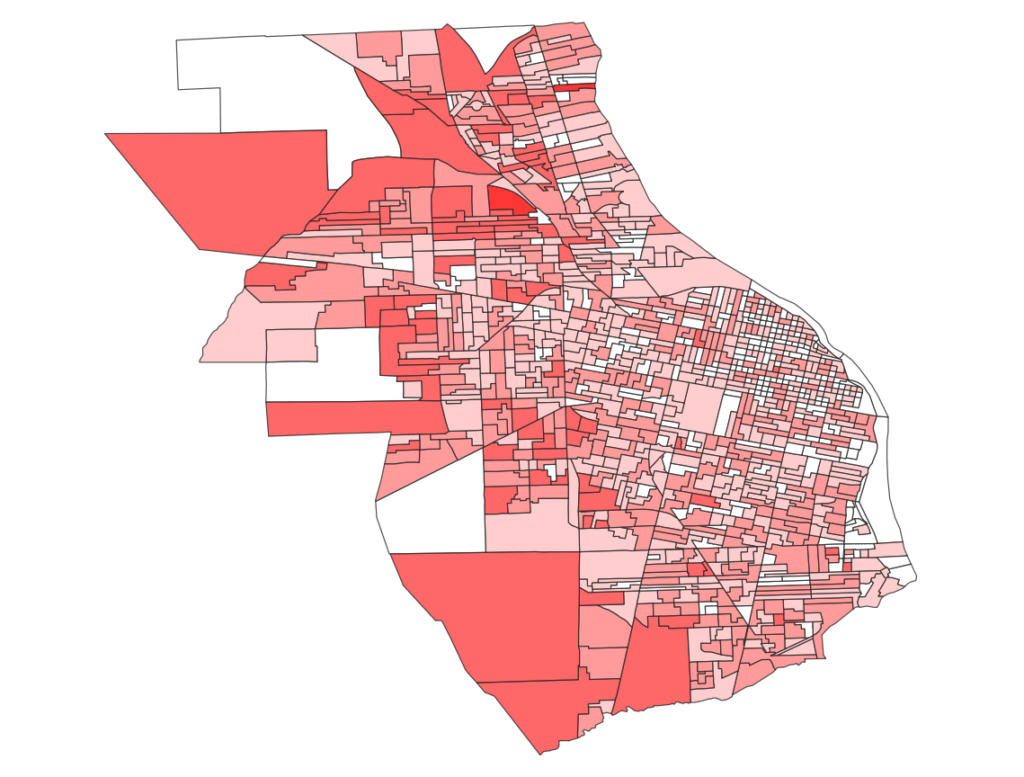

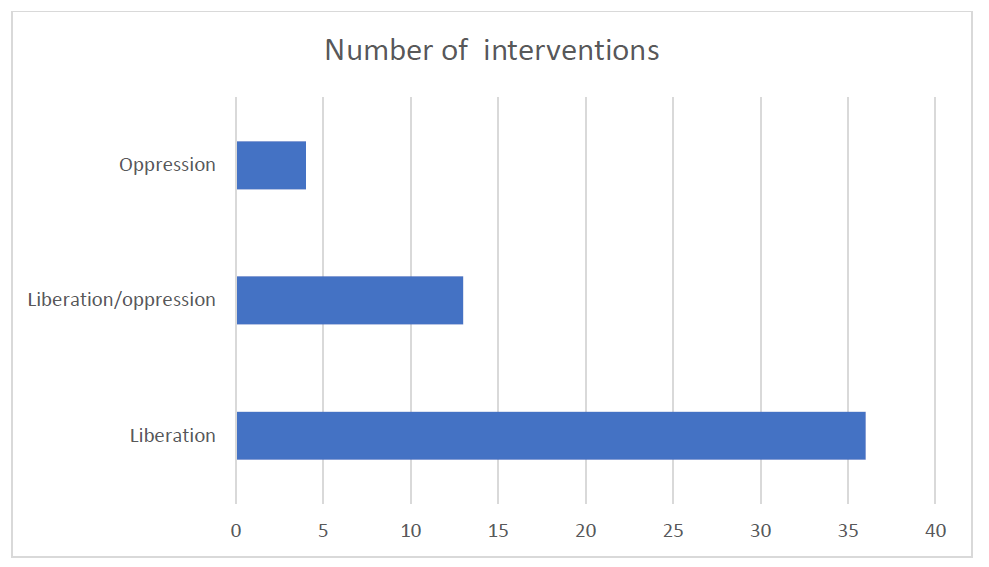

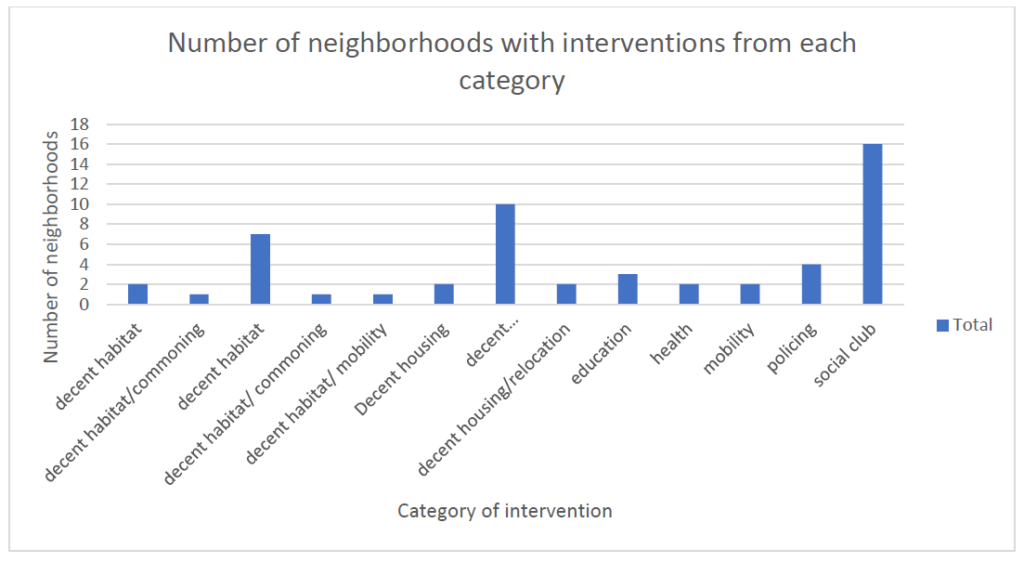

I decided to use the core statement of the Plan Abre as “an integral strategy of intervention sustained on the coordination of different areas of the Social Cabinet of the Provincia de Santa Fe and local governments, with the purpose of recreating social links in neighborhoods (barrios) of Santa Fe, Rosario and Villa Gobernador Galvez”. How can this statement be rephrased?

The Plan Abre is an integral urban intervention recreates social links in the barrios

- Hidden assumptions:

The problem with the barrios relies on the deterioration of social links and their “enclosure”.

Social links depend on formal urbanization, which means opening the barrios.

Social links are deteriorated or inferior only in the barrios

- Image and metaphors:

Barrios are closed places with a lack of social connections.

Barrios as problematic spaces in opposition to other urban spaces

- Object: the barrio is intervened, its inhabitants are not active in the core statement

- Subject: the state is the one acting upon the barrios

- Verbs: recreate. There is a need to transform the social relationships happening in the neighborhood, either disappeared or not adequate

The barrios already have a vivid and complex social life going on due to the structural inequality they experiment in connection with the city. Urban interventions trying to act upon social relations obfuscate the material issue while rejecting existing possibilities implemented by the inhabitants

- Hidden assumptions:

The problem relies on material inequalities not culture.

Social life in the barrios is different because of the structural inequality their inhabitants experience. It is complex – not correct or incorrect.

The relations between barrios and other spaces is linked to structural inequalities.

- Image and metaphors:

The multiplicity of social relations in the barrios – mutual aid, organizing but also competition for resources, violence and informality.

Experience of the inequalities

- Object: the barrio, the action of the state

- Subject: the inhabitants

- Verbs: Go on – social relations are a continuous process, they do not disappear or appear but are transformed through time and space.

Act upon and reject – the state tends to try to organize social space disregarding inhabitants knowledge and experience.

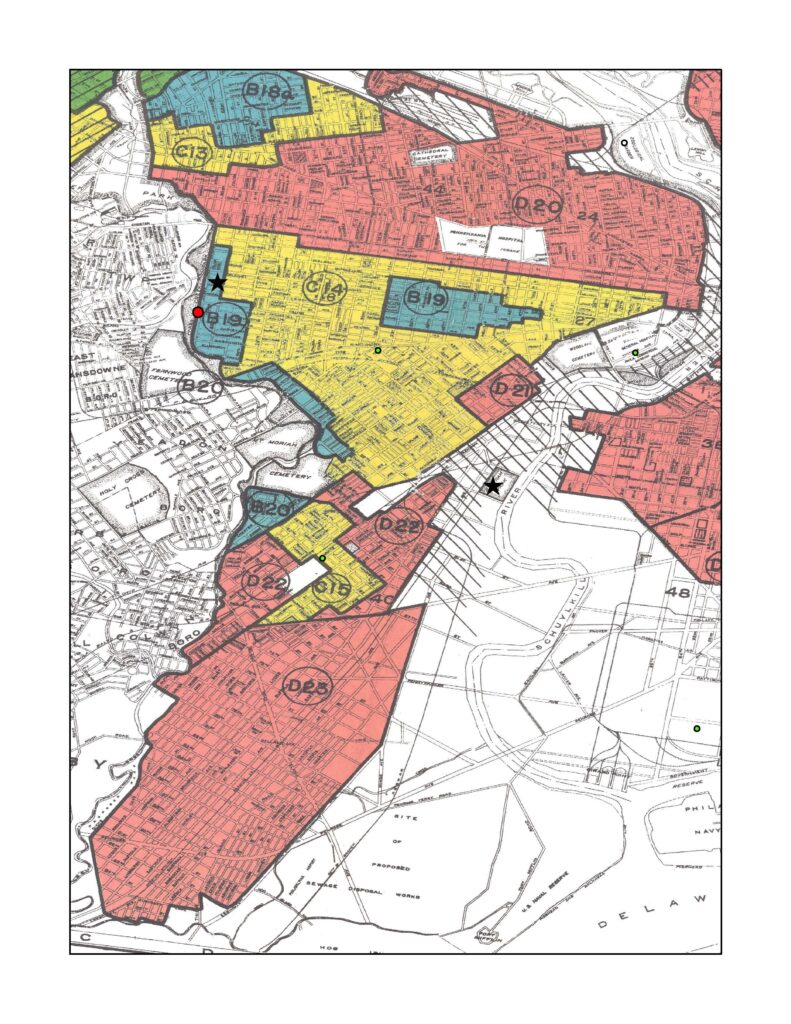

This method has been helpful to analyze the narrative about opening – the hidden assumption is that neighborhoods are closed, separated from the rest of the city. So far I was focused on questioning the action of opening asking how? For who? With what purpose? The Iceberg exercise made me realize that there is a previous question to address which is why does the state consider that these neighborhoods are closed? It also brings me back to Gago’s analysis about the multiplicity of the links between the villas and the rest of the city. She indeed shows how much of the work realized in the villa or by the villeres sustains social production and reproduction in the city. This work also has a lot to do with the work of care that is produced within the city, inscribing the villa as specific places within the urban infrastructure of care. In that sense, the conception of a dual city with open territories as opposed to closed villa is absolutely untrue.

Another element that I started paying more attention to thanks to the iceberg is the focusing on the idea of “recreating social links” in the barrios, hence centering the problem on a social issue rather than a material one. This is also contradictory with the idea of an integral approach to develop public policies. Why does the State promote the idea of the absence or inadequation of social links in the barrios while it is very obvious that networks of solidarity, alternative economy and care are so central to their social reproduction for instance? Other kinds of social relations also exist under the form of political affiliation and activism, as well as violence or conflicts of course. Why is it then that the State seeks to “recreate” social links? What kinds of links are imagined here to be more desirable?

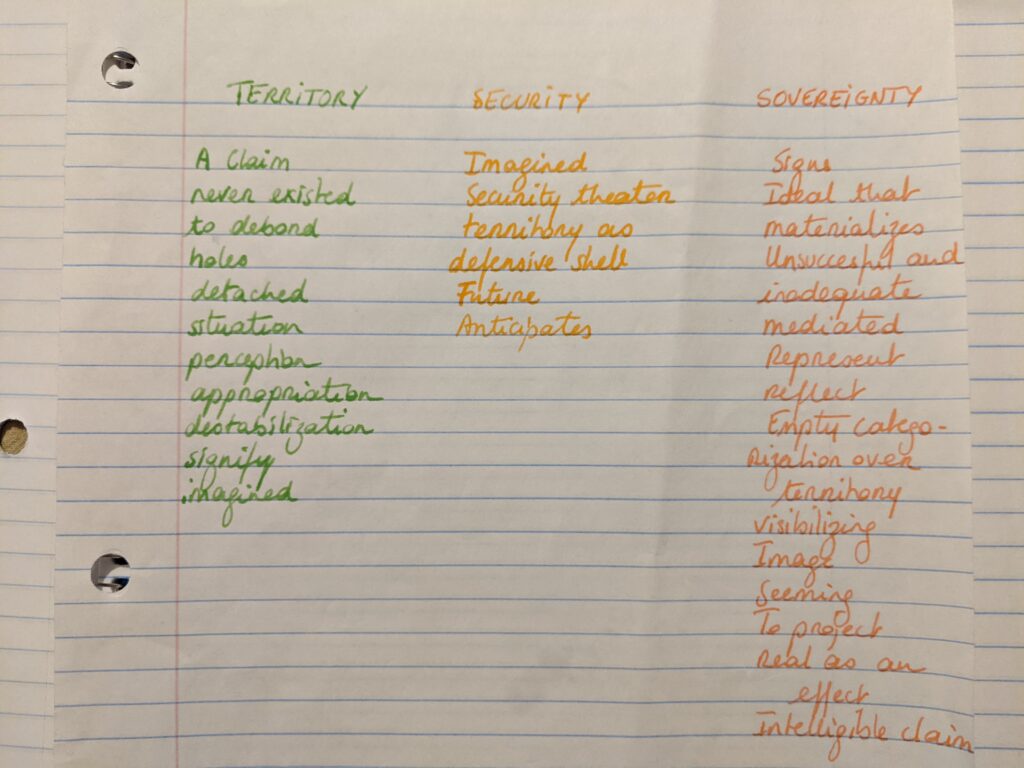

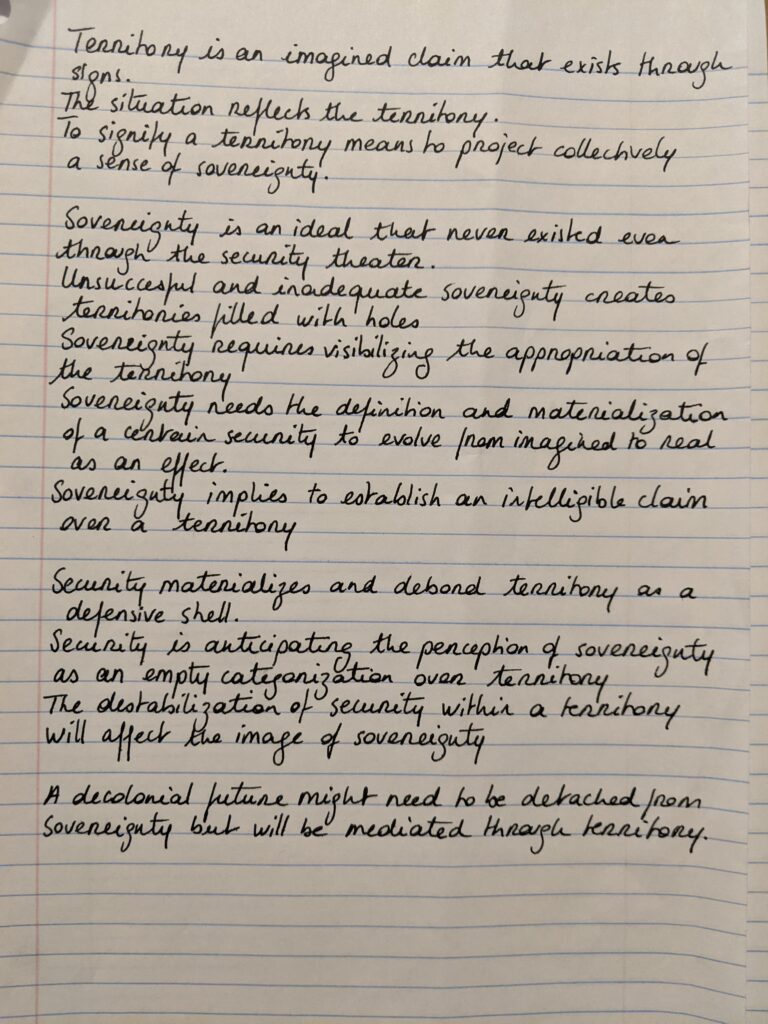

These are definitely questions I will have to pay attention to while developing my research questions. Thinking about these new interrogations through sovereignty, territory and security, I would say that I am now focusing on how problematic social relationships are spatialized through this Plan and its narrative, creating territories with lack of social relations or unacceptable social relations. Security is reduced to a social problem, not a material one. Sovereignty is expressed through the action of opening – implying that the closeness of the neighborhood is a problem for the State while completely ignoring its role in the so-called separate status of these territories. IN contrast, we could problematize around the forms of security produced by the community in Barrios that suffer from abandonment by the State. These networks organized by the population itself speak about a counter-sovereignty, or rather a competing sovereignty.